Malted barley is one of the most important ingredients in whiskey, used for nearly every style in the world from bourbon and rye to — of course — single malt. A millennia-old process, malting unlocks enzymes that make barley more easily fermentable, and that assist in converting the starches of other grains to sugar. Essentially, malting makes the grain — which is almost always barley, though other grains can also be malted — believe it’s been planted in the ground, preparing to grow. It gets steeped in water, then left to dry and germinate to the point of sprouting, at which point growth is sharply stopped with heat.

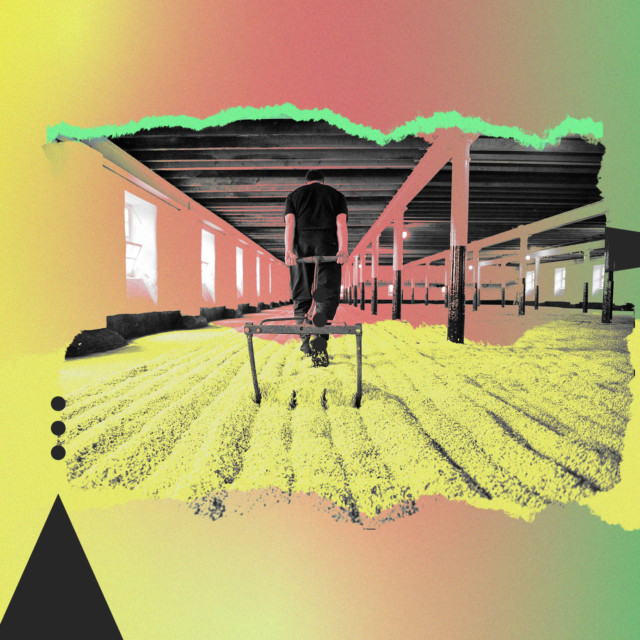

Until the 20th century, malting was a hands-on endeavor, usually requiring a large floor for the germination process, many workers to regularly rake the grains to prevent rot and tangled roots, and a kiln for drying. The labor was backbreaking, with workers often suffering a repetitive strain injury called “monkey shoulder.” After industrialization entered the process widely by the mid-20th century, many distilleries closed their on-site maltings.

These days, commercial malting facilities supply just about every whiskey brand in the world. But a few distillers continue to make their own malt, insistent that it’s worth the effort. “It’s about tradition,” says Simon Brooking, senior ambassador for the Laphroaig and Bowmore distilleries, which both still use malting floors. “And so much of whisky making is about the passing on of tradition.”

Read More on VinePair